Articles

These writings are a synthesis of my own personal experience, research and professional insights.They reflect the things I have seen, people I've spoken to, or things I've done, and are sometimes combined with personal research or learning I have conducted.If you would like to discuss the material in any of the articles below, or suggest ideas for new ones, I would be very happy to learn from you.Please feel free to reach out to me via email or LinkedIn.

How I Learnt To Connect With My Patients

Written: 2nd July 2023

Author: Muhammad Ibrahim

Introduction:Loneliness is an enduring phenomenon permeating our society, often overlooked yet profoundly felt. I witness it daily within the wards of our hospitals, in the faces of patients who lay alone, with no visitors or someone to talk to them beyond the necessity of their presenting conditions. During my clinical placements, I have frequently come across patients who seem to wish for greater interaction, those who possess a wealth of knowledge and experience, yet remain unheard due to the lack of a listening ear. These individuals are part of a silent, suffering majority, unseen by the very nature of their situation.For healthcare practitioners, the practice of connecting with the patients we serve, acknowledging them as social beings, is a crucial element of the care we provide. This connection, this art of communication, should be considered a form of therapeutic intervention, akin to medications or medical examinations. Unfortunately, loneliness is becoming increasingly common in our society, particularly amongst our growing elderly population. Thus, it is essential that we, as healthcare providers, good Samaritans, and members of society, commit to genuinely connecting with one another, offering meaningful interactions that might otherwise be absent in a person's life.My Experience:When I first started seeing patients during my third and fourth years of medical school, I found it challenging to connect with them. Many of them were older than me, came from different cultures, faiths and lifestyles. I didn’t know how I could approach a conversation. Part of the problem was that I felt like I did not have any value to give to them and I genuinely felt like I was wasting their time. I was also blissfully unaware of the loneliness they might have been experiencing, and so I didn’t feel the need or motivation to do strike up conversation.However, as I witnessed more and more interactions with patients, I recognised that understanding the patient experience was not only vital but also complex and rewarding. It was a value unto itself. The best healthcare professionals around me had perfected this art. They were able to attach, engage, detach, re-engage authentically with every patient they met.Once I had identified that there was a need for patients that was unfulfilled, and that I lacked the required skillset to bridge that gap, I set out to improve myself to do so appropriately. I sought out patients I could converse with easily and utilised these interactions to hone my conversation skills. By discussing their lives, their stay in the hospital, their hobbies, or their concerns, I deepened my understanding of their experiences. This practice allowed me to effectively communicate with a wider range of patients and to provide better care by recognising and addressing their feelings of loneliness. This helped me to advocate for these patients more effectively, improved my understanding of their wants and needs, and also provided more satisfaction for me personally in working with them. I started to feel more comfortable in my interactions, and more confident in what I was saying to both patients and colleagues.In the last week alone, I can recall a strikingly large number of patients who were overtly experiencing loneliness. A memorable interaction I had when I was just beginning to practice my conversational skills was of a man who had presented for a destabilising chronic medical condition. He had no partner, no children, unemployed and was expected to live for 12 to 18 months. During his stay, he had expressed feeling tired and worn down from 'going it alone'. After that morning ward round, I sat with him. The conversation started slowly, with awkwardness from the lack of medical necessity precipitating any discussion. I learnt about his childhood, his enjoyment for fashion and in particular, his fondness for a good pair of men’s dress shoes. We discussed the countries he had visited and the best memories from each. We even argued a little over which country was the best to visit, eventually agreeing to disagree. After this, we discussed some of his underlying concerns and worries related to his treatment, and I reassured him where I could. He thanked me for conversing with him, and let me know that he very much appreciated it. This man, who had initially treated me with the courteous distance that patients typically do, was very friendly with me for the remainder of his stay in the ward.In any other context, this exchange may be considered trivial, with no grand meaning, outcome or value to it. However, for this patient, at this specific time, this conversation was something that provided an intangible yet very real benefit. It equalised the roles that so often healthcare practitioners fall into, the sick patient and the healthy healer. It also created a more satisfying experience for myself when seeing this person and working on their case, and made the overall experience that much more human.Some statistics:If it wasn’t already apparent, the evidence on the loneliness epidemic is damning. According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, approximately one in three Australians have experienced episodes of loneliness, with many experiencing multiple episodes over time. This has only worsened since the COVID19 pandemic. Living alone, single relationship status, older age, unemployment, poor mental health and male gender are some of the touted risk factors that contribute to loneliness. The subsequent impact on quality of life is significant. Many of these risk factors are prevalent in the patient populations that we see in hospitals, clinics and other such institutes.Concluding thoughts:It is important that loneliness, particularly for the most vulnerable patient populations, is at the forefront of our minds. It is understandable that given the busy professional environments that many of us work in, we do not find the time to connect with those around us and may have even lost the skills or desire to do so effectively. However, it is the prerogative of humans, and especially those in the service of others, to connect authentically with those around us.Building relationships with patients and easing their feelings of loneliness is a skill that needs nurturing. Like any skill, individuals have varying levels of expertise. I started by reaching out to those who seem open to interaction, and gradually expanded my comfort zone. Seemingly trivial conversations made all the difference in how patients perceived their own state of being and the way they viewed me. Initially, I started off by setting myself small goals for each day. These would be as simple as complimenting at least one person throughout the day. These acted like small ‘wins’ that gave me the confidence to progress. When I was comfortable enough, I took on new challenges. I attempted to stay back and talk to at least one patient I had seen on my ward rounds. I would choose the least intimidating, friendliest patient I could find, and talk to them about their life. Eventually, as I gained an interest in psychiatry, I gave myself the challenge of working as a residential child support worker, which is something I could have never fathomed when I had just started out.My experience was an interesting case study (n = 1) of the effects of compounding, starting small and setting achievable targets. I benefit from that every single day, as I feel more comfortable, confident and capable interacting with my patients. At the end of the day, humans are social creatures, and just as we focus on improving other professional skills, we can improve our ability to connect on a human level. This can lead to significantly better outcomes, workplace satisfaction and patient experience.References

https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/australias-welfare/social-isolation-and-loneliness-covid-pandemic

Karhe L, Kaunonen M. Patient experiences of loneliness. Advances in Nursing Science. 2015 Oct 1;38(4):E21-34.

A Caregiver's Experience of Newly Diagnosed Cancer

Written: 13th July 2023

Author: Muhammad Ibrahim*Key details and names were altered, omitted or adapted to preserve anonymity.

In my limited experiences as a medical student and in dealing with patients and their families, I’ve learnt more about the impacts that patient’s conditions can have on their loved ones. I've come to understand more about how a cancer diagnosis doesn't just affect the patient - it permeates the lives of those around them too.On my placements, I was fortunate to be able to sit down and chat with Molly*, wife and caregiver to her husband who was recently diagnosed with cancer, to share her personal experience and draw light to her perspective as a carer. A perspective that can sometimes be overlooked."It all happened so quickly I didn’t know what was happening," Molly shared, as our conversation began. She recalled how it her husband's condition started insidiously, with generalised symptoms that did not resolve. Eventually, he was referred to the hospital. During their stay, her husband went through a battery of tests, many of which went over their heads. She felt that she didn’t know what was happening, why it was happening and what the treating teams were considering to be the working diagnosis. At this point, Molly and her husband felt very confused and bewildered. Coupled with the new and unfamiliar hospital environment, they were very disconcerted with the whole process and began to worry that something was not quite right.After a few days of tests, examinations and deliberation, Molly received an answer. At the time, she had just finished a conversation with her husband about an activity they were planning for the next few weeks. However, as the consultation with the treating physician progressed, she and her husband were told that the investigations seemed to be pointing towards a certain direction. Apparently, the imaging studies depicted what looked like to be a considerably progressed cancer. Upon hearing this, Molly said that she literally screamed. This was "most traumatic experience of her life". The nature of this reveal, the timing, the lack of preparedness was all too much for her, and she says that she has been in a state of shock since.Molly confessed how the news shattered her. "I've been lost since then," she admitted. Her stoic husband, the man she had relied on for the majority of her life, was suddenly declining, and Molly found herself needing to step up for both their sakes. She felt that her life had been swept up, and that the bubble of her blissful marriage had been popped. Molly stated she felt the pressure to stay strong in front of her husband, who could see that she was being worn down by the situation. She commented on the irony of the situation, seeing as her husband was the one who had been diagnosed with cancer.Molly expressed some frustration with the somewhat 'shallow' offers for help. After conversations with many health professionals in a short period of time, she began to feel that many of the discussions around self-care were repetitive, and not very helpful. "Every time I talked to someone new, they would tell me to take care of myself. But I didn't know how." Molly said that instead of suggestions and recommendations, she wished the professionals she had talked to would instead provide an avenue for her to talk and express her emotions. She felt bottled up, and said that many of the things she felt, she couldn't share with her husband because of his critical condition.Over the next few weeks, Molly and her partner found some stability in the ongoing discussions with the oncology team. They learnt about the condition, likely prognosis, treatment options and where they could look to get support. By this point, Molly had reached out to close family members, friends and others including her GP, who referred her to a counsellor.When describing what worked for her and what advice she would give to others in her situation, she commented that "having a space to express your feelings is so important." She said the experience felt as if she was in “a vast field with no borders in sight. You feel lost, like you're treading water”. But as the days and weeks went by, and both she and her husband began to acclimatise to this new normal, she found some comfort in accepting the ambiguity. Her advice to others was to allow themselves to express their emotions, "there's no right or wrong way to feel."When asked what she would prefer and expect from healthcare professionals, she said she would have benefitted from a gentler approach. "When a healthcare professional engages in conversations such as a cancer diagnosis, they need to do it gently and carefully." She also stressed the importance of taking into account the patients' lack of medical knowledge in conversations, as she felt like she has had to learn a ‘whole new world’ of vocabulary to make sense of what is going on. Molly remarked that not knowing what was going on was one of the worst feelings, especially when she began to have a creeping suspicion that something was not quite right with her husband. She said that she wished the communication had been clearer from the start in order to prevent that, and to set appropriate expectations.

My ReflectionHearing Molly's story as a medical student was a unique experience. It forced me to think about life's impermanence and our physical fragility. As a 23-year-old about to graduate from university, many times I catch myself planning for what I’ll do when I enter the next chapter of my life.While it is a fairly reasonable and human thought, I have fallen victim to the mentality of ‘expecting’ that I will have more time, or that I will have a future that resembles the plans I dream of today. Contrasting this with the shattered life that Molly is now living, the irony of the situation is palpable.From Molly, I learnt the importance of family and sacrifice. In the face of fear and uncertainty, she was doing everything in her power to make her partner’s life better. Her very human trait of carrying on no matter what, to me, resembles something suspiciously close to true love. This was a powerful demonstration of our capacity for good in the face of what is otherwise unbearable.As a future healthcare professional going forward, this story will stay with me. This insight gives depth to the patients and families I will see in the future, and will help me to understand a fraction of what they might be experiencing. I will be much more aware of the significant impacts a life-altering diagnosis can have not only for the patient, but their family and carers.

'The Leadership of Muhammad' by John Adair - A Summary

Written: 4th August 2023

Author: Muhammad IbrahimReworded from a Master of Public Health Assignment

Dotpoint Summary

A review of "The Leadership of Muhammad (PBUH)" by Professor John Adair, exploring Muhammad's (PBUH) leadership through social, historical, and theological lenses.

John Adair is an established authority on leadership with over 40 titles and a varied career.

Published in 2010, the book is a 144-page read, priced at $30 AUD, aimed at applying Muhammad's (PBUH) leadership qualities to modern contexts.

Written from a Western perspective, the book covers Islamic history with a focus on leadership, using a blend of anecdotes, scriptures, leadership theory, and hadeeth.

The book is divided into eight chapters, each tackling different aspects of Muhammad's (PBUH) life and leadership, from childhood to adulthood.

Adair posits that good leaders reflect humanistic qualities like kindness and goodness; they also understand individual needs within the group, work towards common goals, and create unity.

The book delves into the historical and cultural aspects of Arabian life, emphasising the dynamics of leadership as shaped by various influences including trade.

Adair contends that leaders are not born but are developed through aptitude, practice, and reflection, and that wisdom and agility are vital for leadership.

Honest character and integrity are highlighted as essential traits for inspiring confidence and trust in leadership.

Adair stresses the importance of leaders sharing in the hardships of their people, leading by example and gaining moral authority.

The concept of 'asabiya' or group spirit is introduced as a critical factor for a group's success, and Adair recommends leaders focus on this to improve morale and performance.

The book presents a strong narrative and alignment with modern theories of servant and transformational leadership but lacks citations and specific focus.

IntroductionThe Leadership of Muhammad (Peace be upon him - PBUH), by Professor John Adair is a complex insight into the leadership qualities of one of humankind’s most pivotal historical figures. In doing so, Adair paints a vivid portrait, incorporating social, cultural and historical contexts with the theological and philosophical elements that surround Muhammad (PBUH).Professor John Adair (born 1934) has published over 40 titles on leadership throughout a varied career that has taken him from Egypt as a member of the Scots Guard, to deckhand over the Iceland seas, to hospital orderly, senior military lecturer, leadership training advisor and the professor for leadership studies at Surrey University (1). He has many achievements, prizes and recognitions worldwide for his contributions to the field of leadership (1).The Leadership of Muhammad (PBUH) was published in 2010, marking his 34th publication. Available for approximately $30 AUD at the time of writing, the book is comprised of 144 pages, making it a very digestible read at a reasonable price. Adair aims to distil core concepts of Islamic canon with pre-existing Arab Bedouin culture into universal ideas of leadership that can be applied to the modern day. The aim of this review is to discuss the merits and flaws of the ideas expressed, as well as the methodology and evidence used to support them.

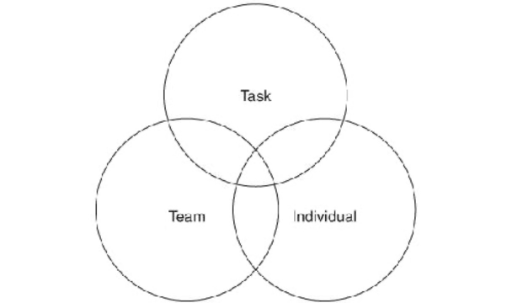

General featuresThis book is written as a western perspective on Islamic history, with a focus on leadership. As such, it is an accessible read for the wider audience. Adair divides his book into 8 chapters, not including the introduction, conclusion and appendix. Throughout his book, Adair uses a mixture of personal anecdote, scripture, leadership theory and hadeeth (systematically recorded accounts and narrations of Muhammad PBUH). Adair attempts to organically create his story using multiple sources and methods to instil upon the reader the global qualities of leadership, using the pristine example of Muhammad PBUH.The first chapter introduces the infancy, childhood and upbringing of the prophet (PBUH) while discussing particulars of Bedouin Arab culture. Using key historical conflicts, Adair surmises that leaders should be a reflection of the traits that are required and/or valued in their groups. He creates a simple deduction stating that all organisations are comprised of humans, and the best leaders reflect humanistic qualities such as “goodness, kindness, humaneness”, implying that leaders should aspire to adopt these values.Chapter two, titled ‘The Shepherd’, reflects the young adult life of Muhammad (PBUH). His work as a shepherd is highlighted, and compared to the prophet-shepherds of the past such as David, Moses and Jesus (Peace be upon Them). Quoting Psalms and referencing Homer, Adair clarifies that the shepherd represents the most significant metaphor for leader in the Abrahamic tradition. Adair notes the importance of the shepherd’s intricate attention to their flock, their adoption of shared group risk and the key role they play in providing group unity while managing subdivisions. Adair denotes the complementary nature of a leaders’ knowledge of individuals within their group, with the leadership they display from the front.He divides the task of shepherds (leaders) into three ‘circles’: 1) to achieve the common task, 2) to create unity and 3) to address individual needs of the group.This can be seen in a figure provided within the book below (figure 1):

The third chapter addresses community dynamics and geopolitical significance of the Arabs of Makkah, Muhammad’s (PBUH) place of birth. Adair discusses how leaders in time past were reliant on strong personalities, courage and wisdom in judgment in order to retain trust. He uses the concept of caravans and trade journeys (important to the economic power of Makkah) to illustrate how leadership is a dynamic concept, involving the shaping of a group’s ‘journey’ towards their shared objective. Adair also focuses on how those in positions of leadership are not always capable of leading, and that these leadership attributes can be developed and nurtured (as referenced by the upbringing and shepherd work of Muhammad [PBUH]). Adair concludes this chapter by arguing that wisdom is knowledge used judiciously at the right time, a skill agile leaders must master. He reaffirms leaders are not born, but made through “aptitude, practice and reflection”, all while in the overall spirit of service.Chapter four begins with further detail on the history of Arabia, as well as Adair’s own experiences in the region, and the intricate relationship between Arab culture, the desert and their camels. He then discusses qualities of various Bedouin leaders, combining the qualities mentioned in previous chapters with generosity, experience, craftiness and diplomacy. He describes examples of how Bedouins did not verbally enforce hierarchy, choosing to use first names whilst avoiding overfamiliarity. He summarises chapter by stating that harsh conditions require leaders to work together with their followers, and that they cannot differentiate themselves too greatly from their group. Adair also highlights the necessity for groups to have a leader, and for leaders to have approval of the group.The next chapter, titled ‘Muhammad, the Trustworthy One’ begins by mentioning one of Muhammad’s (PBUH) titles, al-amin, the trustworthy one. He links this to the importance of honesty and character to leadership. In Adair’s eyes, the best leaders placed themselves on equal footing with their people. This was characterised throughout the leadership of Muhammad (PBUH) and his people’s enduring trust in him. He summarises this chapter by concluding that leaders inspire confidence through honesty; firmly stating that leaders lacking integrity are not truly leaders at all but instead individuals who mislead.Chapter six deals with the ways in which leaders share in hardship with their people. Adair uses Muhammad’s (PBUH) examples of working alongside his community to inspire their efforts and actions. As a result of this and his prior upbringing, Adair posits that Muhammad (PBUH) had a keen ability to glean insights from those he led, and was always ready to take advice. Further, he would be the first to take on unpleasant responsibilities. Adair concludes the chapter crystallising the message of leading by example. He affirms that moral authority that is provided to leaders by partaking in hardship, not those who use their position to entomb themselves away from group discomfort.The next chapter, titled ‘Humility’, discusses matters of Islamic theology and pre-Islamic Arabian history. Adair does not shy away from addressing the overt utility of Muhammad’s (PBUH) ‘monopoly’ on prophethood, arguing the necessity for a singular leader. The author argues there is inherent utility in this concentration of leadership, which was instrumental in establishing unity and guiding people towards a singular direction. Adair aligns this with the essence of Islamic faith, ‘Tawhid’, the belief that there is one God/Allah. He argues there is an inherent humility in this notion displayed by Muhammad (PBUH), who at all points defers any true authority to the divine. Quoting the Quran, Adair reaffirms the important of humility, and then links its value to leadership, particularly when leaders become arrogant, harsh or angry. The key principle of moderation, particularly between firmness and kindness, is cited as an important value in this regard.The final chapter is titled ‘From Past to Present’, and details further Muslim leaders that reflect the Islamic form of leadership. Adair again extolls the importance of moderation, practicality and earning the loyalty of the people. He posits that successful groups carry an attribute of ‘asabiya’, which is loosely translated to a ‘group spirit’ or ‘feeling’. Those groups with more asabiya tend to be more successful than those without. Adair touches on how groups tend to adopt a psyche superimposed upon that of each individual. Poorly aligned groups have poor asabiya, which leads to in-fighting and discord, making them less effective.Recalling to three areas of need (figure 1), Adair argues that groups with appropriate alignment or asabiya experience better morale, reduced burnout, greater performance and a sense of achievement. He further states that deficiency in any one area impacts the other two directly. Adair acknowledges the magnitude of managing this, and implores leaders to treat individuals in their teams as leaders, effectively becoming a ‘leader of leaders.’ He then provides some semantic detail, and reiterates the key points of his book before concluding with a humble word to his readers.

CritiqueAdair weaves a strong narrative regarding his personal views on leadership, enmeshed with historical, sociopsychological and theological arguments. Ironically, he uses ‘premodern’ sources to mirror ideas in current modern leadership theory. Moving away from 19th and 20th century ideas of leadership, Adair imbues his book with concepts of ‘servant leadership’, positing leadership is largely learnt and not wholly inherent (2). His position largely reflects the postmodern transformational view on leadership, with leaders adopting humane values, empowering their group, inspiring their followers and fostering individual development to bring about increased group effectiveness (2-4). The contemporary focus on the notion of ‘authentic leadership’ reflects Adair’s own views in the book regarding the necessity for leaders to be transparent, ethical and strong communicators, and agree well with much of what he argues (4).Overall, Adair shies away from a prescriptive, singular theory for leadership. Rather he focuses on a contextualised ‘needs and outcomes’ or ‘skills-based approach’, where he identifies traits, processes and behaviours that facilitate both individual needs within groups, but also work to enhance overall outcomes. Many of these ideas are replicated in corporate and healthcare settings, and their facilitation can lead to improved staff turnover, growth, satisfaction, performance, commitment and efficiency (5).Negative criticisms of Adair’s book arise not from his ideas on leadership, but more so the methodology and resources he uses to arrive to them. Adair for the most part does not cite sources regarding the biography of Muhammad (PBUH), or the English translation he uses for Quranic verses. There is potential for Adair to quote ‘weak’ or ‘rejected’ aspects of the biography, including apocryphal events that are not accepted by wider Muslim scholarship. While this is not a scholarly text and Adair is not a Muslim scholar, it is important for biographical elements to be appropriately cited as part of academic due process, especially if they are being used to draw conclusions. Factual inaccuracies that arise from this put into doubt the veracity of Adair’s claims, even if the ideas hold true on their own.Another criticism is the lack of overall focus in the book. While this may be due to author intent, in order to provide context Adair loses specificity in his writing. In a book of 144 pages, nearly half the book does not focus on either leadership or Muhammad (PBUH). Greater focus would have yielded more direct information about the titled topic. As a result, the book reads more generally, with less of a focus on leadership theory than one might expect. There is also some ambiguity in how Adair may see many of his generalised ideas applied, but in the concise and non-prescriptive fashion of his book, that could be intentionally left to the reader’s interpretation.

ConclusionAdair crafts a commendable text in concise fashion that combines many aspects of Islamic and Arabian leadership, through the linchpin of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). For those interested in history, culture, theology alongside leadership, this book packs a useful amount of information for any leader, although Adair leaves the reader to their own devices in terms of its application.

Bibliography1. Biography. Webpage. John Adair Leadership and Management TM. Accessed 14 Sep 2023, http://www.johnadair.co.uk/index.html

2. What is leadership? McKinsey & Company. Accessed 15-Sep-2023, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/mckinsey-explainers/what-is-leadership#/

3. What Leaders Really Do. Harvard Business Review Accessed 15 Sep 2023, https://hbr.org/2001/12/what-leaders-really-do

4. Dinh JE, Lord RG, Gardner WL, Meuser JD, Liden RC, Hu J. Leadership theory and research in the new millennium: Current theoretical trends and changing perspectives. The leadership quarterly. 2014;25(1):36-62.

5. Gilmartin MJ, D'Aunno TA. 8 Leadership research in healthcare: A review and roadmap. Academy of Management Annals. 2007;1(1):387-438.

Navigating a Career in The Early Stages: Insights from Dr. Sanil Rege

Written: 18th November 2023

Author: Muhammad Ibrahim*Adapted from an interview

Introduction

Navigating a career in a field such as medicine can be a difficult process. As someone who is at the start of my career, it is especially daunting facing the multitude of choices that can lead me down the variety of career pathways. Speaking with those who have already traversed these routes has been especially informative. A useful by-product of my medical rotations has been to give me access to established or establishing individuals, allowing me to learn about the steps they have taken. This has been a very insightful way to appreciate what might come next for myself.In light of this, I had the privilege of speaking with Dr. Sanil Rege, a seasoned psychiatrist with a rich background in both public and private practice, as well as in research, medical education, business and leadership.I wrote this short article in order to summarise, explore and share Dr Rege’s insights and advice, particularly for those interested in medicine, psychiatry, entrepreneurship, and lifelong learning.

Dr. Rege's Career Path and Philosophy

In his own words, Dr Rege’s journey wasn't a straight path.Having grown up in Dubai, completed medical school in Mumbai, worked in psychiatry in places ranging from the UK, New Zealand, Egypt and Australia, Dr. Sanil Rege has cultivated a truly global palette of experiences and skills.Once moving to Australia, he started out his career in the public sector until 2013, before making a transition to full-time private practice and education. Dr. Rege has also worked as a locum across Australia and held an academic role as an Associate Professor in Western Australia.After moving to Melbourne, he enrolled in an MBA programme at Melbourne Business School. He decided to cease his studies after completing six subjects in order to apply what he learnt through his own projects.Practicing what he preaches, his career reflects the complexity and variety that a career in medicine can provide. This reflects the idea that there's no set linear path in medicine; rather there are only opportunities, and it is simply a matter of choosing which ones you want to pursue. With regards to psychiatry in particular, Dr Rege is a strong believer that it is a field ripe with opportunities and growth for those willing to explore.

The Importance of Being Open to Opportunities

One of the key takeaways from our discussion was the importance of being open to opportunities.

Dr. Rege highlighted that he has noticed it is very common for those starting out in their careers to seek prescriptive advice. It can be very tempting to follow in the footsteps of a senior who seems to be in the position you would like to be in one day.However, Dr Rege believes it is crucial to understand that circumstances change. What worked for one person may not necessarily work for another. What might have been appropriate in 2010 may not work for someone in 2023. Instead, the goal should be to learn and grow, as there are no wasted opportunities. Dr. Rege's own career, which he describes as seemingly 'random' at times, is a testament to this philosophy, where he proposes a process oriented mindset to approaching challenges.This ties in with the importance of having multiple mentors and sources of knowledge. Dr Rege believes that relying on a single mentor can lead to a biased or limited perspective. By seeking advice from various sources, you can synthesise your own understanding and approach to your career. This is particularly important in a field as diverse and evolving as psychiatry.

The Role of Education and Skill Development

Throughout our discussion, it became very clear that Dr. Rege is a strong advocate and practitioner of ‘broad-based learning’. He emphasised the importance of acquiring a range of skills, both general and specific.While he initially focused on psychiatry, he later expanded his skill set to include business management, marketing, website building, video editing and so on. Nearly all of these skills fell outside of the range of what might be considered ‘typical’ for a medical practitioner, however almost all of them have been incorporated into his practice.These skills may not always seem directly relevant, but they often prove invaluable in unexpected ways. He believes that innovation usually arises from the overlaps between multiple areas of knowledge, and that as professionals we should endeavour to have broad bases of knowledge to draw from.This is something he put into practice when applying basics of medical marketing and business management to his own private practice.

Overcommitting

Dr Rege cautioned against a tendency for people to overcommit to opportunities, especially early in one's career. While it can be tempting and is driven by the desire to ‘do more’, doing 10 things at once usually means you end up doing nothing well. Rather, Dr Rege advocates for selective commitment to opportunities, alongside the necessity of aligning these opportunities with a core vision or passion. This alignment helps in making informed decisions that contribute positively to your career trajectory.A big part of this alignment requires an understanding of the ‘basic’ direction of where you want to go. For many, simply the desire to learn and expand their knowledge can be a very powerful way to align themselves with opportunities. Prioritising those experiences that maximise learning, exposure to new ideas and consolidate core principles is a useful and consistent way to make the most of your limited time.

Recommended Resources

Dr. Rege recommended several resources for those interested in broadening their horizons. These include the book "Good to Great" by James Collins and learning about the Japanese concept of Ikigai, which explores the intersection of passion, skill, and career. He also suggested "Poor Charlie’s Almanack" for multidisciplinary learning and "The Medici Effect," which discusses how innovations often occur at the intersections of different fields of knowledge.

"Good to Great" by James Collins

"Poor Charlie’s Almanack" by Charlie Munger

"The Medici Effect" by Frans Johansson

"Principles" by Ray Dalio

My Thoughts

This conversation was very useful as someone starting out in my field. As an individual who worries often about making the ‘wrong’ move, it was nice to be told that most experiences tend to offer some benefit down the line. It also highlighted the importance of resisting the temptation to have a ‘one-track mind’ when it came to career focus.This advice aligned with that of other mentors, who have guided me to be open with regards to my speciality of interest. I have been told that it is important engage with every rotation I work in with keen interest, as the skills I learn will stay with me wherever I go. Dr Rege’s advice also ties into the notion that I should spend the first few years as a junior doctor exploring my interests and developing ‘core’ skills. Specifically, I have been cautioned against narrowing myself down one particular path too quickly.As someone who prefers certainty and planning out my steps well in advance, this advice can fly in the face of my natural instincts. However, I find that as I increasingly become committed to ‘not committing’, I open myself up to learning more wherever I am. Where once I would feel that a particular experience is ‘boring’ or ‘wasted’ since it does not align with what I see myself doing, now I might approach that same experience with the attitude of trying to glean something of lasting utility. This has been a useful and interesting change in approach, and it is reassuring to see that the advice I receive supports this.My discussion with Dr. Sanil Rege was a very interesting experience, offering useful advice for anyone interested in psychiatry, medicine or starting their career in a broader sense. His journey shows that while the path may not be straightforward, it is filled with opportunities for those willing to learn and adapt. Whether you're a student, a young professional, or someone considering a career change, these insights can serve as valuable guidance on your own career journey.